Take off your glasses

In 1994, I sat in the office of a New York City typesetter. This guy was one of the old saws who'd been around when typesetters were laying out type with cold lead. He was running a small imagesetting shop in midtown Manhattan and was offering me leads on where I could find work.

The desktop publishing revolution had been kind to me. I had been taught the rudimentary aspects of QuarkXPress to lay out our college newspaper and soon went on to master every aspect it, nearly devouring Quark's manual back to back. I loved typesetting. It was fun.

As sat in this guy's office, I remember getting caught up in how useful DTP was, how much more efficient its workflow was to what had come before it. No need to set physical type anymore—you just typed it into a computer. Wasn't that cool? This guy's take was quite the opposite: "I hate what desktop publishing has done to this industry." I can't remember his exact wording, but the gist was, I remember the old way. I liked the old way. But the old way doesn't make money anymore and I hate being forced to change.

I wasn't unsympathetic—everything he had known and loved about his industry had shifted underneath his feet. I felt sad for him, but... wasn't he able he see how much easier his life could be? Did he really want to return to a less efficient system simply because he wasn't as comfortable with newer methods? Instead of doing half as much work under the old system, he could do three times more work with the new system. As with any new tool, there was a learning curve, but wasn't there an intrinsic value from having access to better tools?

This resistance is typical across any profession undergoing change. The digital age affected typesetting in the '90s, the music industry in the '00s, and now it's hitting the movie industry. Unsurprisingly, my last article on how to make money even if you give your films away for free hit some resistance some filmmakers. Miles Maker had the most eloquent response:

To steer the focus away from making memorable movies and toward merchandising sickens me. Indies are already struggling to complete their beautiful little films to pay people and achieve higher production values. Where does the manufacturing revenue come from? And yes products are replaced by better products, but a film is a unique visual journey; an original experience all to itself... my body of work must hold value to sustain growth, or I will be forced to churn out lower quality FREE content at a hellish pace to support my life's endeavors.

I don't disagree on any particular point. Merchandising has taken a more prominent role, perhaps even in competition with a movie's unique visual experience, and that also sickens me. It's already hard enough to pay cast and crew to make movies, and now the possibility of offering up our films for free doesn't seem to make any sense at all. We all want consumers to pay for the experience of the film, and it feels like long-term growth is unsustainable under a FREE model.

In this whole debate, my own feelings on the matter have been drowned out: if I could wave a wand, I would never make films free. I think piracy has been enormously disruptive to the entertainment industry... however, despite my strong personal convictions, I also realize that stopping piracy is a Sisyphus-tic pursuit and the only way forward is learning how best to adapt to the changing market, i.e., how to compete.

I also feel strongly that anyone refusing to acknowledge the direction of the wind will be blown out to sea, and rightfully so. Pay American workers too much and American companies will outsource to cheaper foreign workers. Yes, it's tragic, it affects lives, it's awful. But it's also how a free market economy functions—those who don't adapt quickly enough perish.

To address Miles' point, long-term growth might very well be unsustainable under a free model... if we assume a very narrow definition of what is trying to be sustained, i.e., producing and selling feature films at their current budgets for current prices. That may very well be unsustainable (though a free model might be more profitable if we figure out the right formula). The variables, however, can be changed—cheaper movies can be produced and movies can be sold for less. Yes, American filmmaking might be unsustainable, but the ludicrously inexpensive filmmaking industry in India will thrive unabated. If America's film industry cannot sustain itself in its current form, it will either adapt by lowering its costs, by dropping prices, or it will stop.

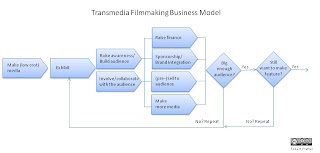

The way things are going, I suspect the American film industry in its current state is indeed slouching toward unsustainability. This is why I feel the definition of what is sustainable is too narrow—regardless of what we want our role to be as filmmakers, the market is telling us all that it doesn't just want films, it wants stories. The market wants storytellers. Feature films are but one product fulfilling that market need.

Many average filmmakers will be too obstinate or unwilling to see the glaring truth: the traditional role of filmmaker is expanding beyond its current skillsets to pave the way for a hybrid filmmaker/producer/publicist/storyteller. Only the most astute among that group will flourish in the coming years... and we'll hear Old Guard filmmakers whine more frequently about how they can't seem to compete with free (a red herring—the bottled water industry does quite well competing with free). The period of vetting is already upon us as some big studios close up shop. Independent filmmakers, already pushing their fixed costs as low to zero as they can, will migrate toward wikinomics-style filmmaking where many cast and crew volunteer their time for its own sake, perhaps preferring to take percentages on the back end instead of a basic salary. Yes, that will devastate the industry as we know it now, but it seems to me that the writing is on the wall.

No matter what my own personal feelings are about piracy or how the entertainment industry has changed for the worse, nobody can legitimately condemn a future they don't yet know: horse and buggy drivers would have been astonished at how much more efficient (and "better") transportation is today. Likewise, the next generation will likely one day say to us, "You used to PAY for movies?!?" and then laugh themselves silly. We'll all pine about a childhood as alien to them as living without electricity is to us now. The future of entertainment will not always be as it currently is, but its next iteration—perhaps weaving interactive narratives across multiple media to create fascinating stories—could be far richer, more engaging and even more meaningful than a feature film could ever do by itself. That might mean feature films become less ubiquitous in the entertainment spectrum, but that's not really up to filmmakers. Only the market can decide something like that.